The word “evolution” brings to mind a lot of things, many of which are directly connected to a guy named Darwin. But, the overall impression of the word is that it happens over massive amounts of time. It happens so slowly it can only be noticed or charted over hundreds or thousands of years. You can only see it through that lens. It doesn’t happen in a year, much less overnight.

With that in mind, I’ve been watching a lot of baseball and will continue to do that as long as we have games to watch in 2020, and the rapid evolution of the game continues to be remarkably startling. In many ways, it bears little resemblance to the game I grew up playing. Is that a bad thing? Not at all, in my opinion. I’m not a stick-in-the-mud type who only revels in the “good old days.” I’m into transformations, information, knowledge, science, and all of that, even when it comes to sports. Baseball, for some reason, just seems to be the epicenter for these new approaches and techniques. That’s fine by me, and it gives me new interest in watching games on television since we can’t be there in-person. I enjoy watching what pitchers, hitters, fielders, managers, and coaches are doing now. The evolution is ongoing, and it’s happening right in front of our eyes.

When I was a kid, things like batting stances and swings were always addressed and created via the “whatever feels most comfortable for you” theory. Seriously. Like a lot of kids, I found various stances that were comfortable by copying Major League guys I admired. I thought Orlando Cepeda was one of the coolest dudes in the world, in every regard, but his closed stance (meaning his front foot was way closer to the plate than his back foot) was impossible for me to master, despite the fact I desperately wanted to be Orlando Cepeda. That was a sure sign that I could never be Orlando Cepeda.

Finally, by high school, I did actually settle on what was most comfortable for me. I kept my hands low, almost at the belt and tried to completely relax. That worked great when I faced pitchers who threw the ball straight and not very fast, but I certainly had to adapt the whole concept as I moved up the ladder to college and pro ball. I had a series of triggers (mostly based on where the pitcher was in his delivery) that I’d implement to make sure I had the bat back and “loaded” when it was time for the swing to move forward. It was complicated, and hard to replicate swing after swing.

Then, when guys started throwing serious heat, I’d have to “cheat” a little to get the swing started before I ever saw the pitch at all. There was a lot going on in that swing, and it was easy prey for guys that threw hard but could then also change speeds. Basically, I was pretty much always guessing what pitch would be next. If I guessed right, good things could happen. If not, it wasn’t pretty. That’s why hitting a baseball is hard and you can still see Major League hitters miss pitches by two feet. I saw one two nights ago. A very good big league hitter swung at a curve that landed a foot in front of the plate. How is that possible? Because he was fooled. Hitting a baseball is really hard.

College ball. Hands low, knee cocked, mind lost.

(For the record, the photo to the right was me hitting at Western Carolina University, home of the Catamounts, which is a world-class sports nickname. I did get a couple of hits in this game, off a pretty good pitcher. I also appear to weigh about 150 pounds.)

So, over the course of 100 years, the art of coaching the act of hitting a ball was a broad stroke of endless pieces of unproven advice, and what that spawned was an equally endless variety of batting stances. Babe Ruth, with his feet basically together at the back of the batter’s box, hands low. Then he’d sell out and stride into every pitch with a mighty swing. Yaz with his bat way above his head, held straight up. Rod Carew in his peekaboo crouch, with the bat laid parallel to the ground behind him. Joe Morgan with his “chicken wing” flap as a trigger. Willie Stargell with his bat loops before he got set. Everyone had a different approach. The only universal rules were “See the ball, hit the ball. Take a round bat and hit a round ball as squarely as you can.” And those names I just listed were pretty good players. You’ll find them all in Cooperstown.

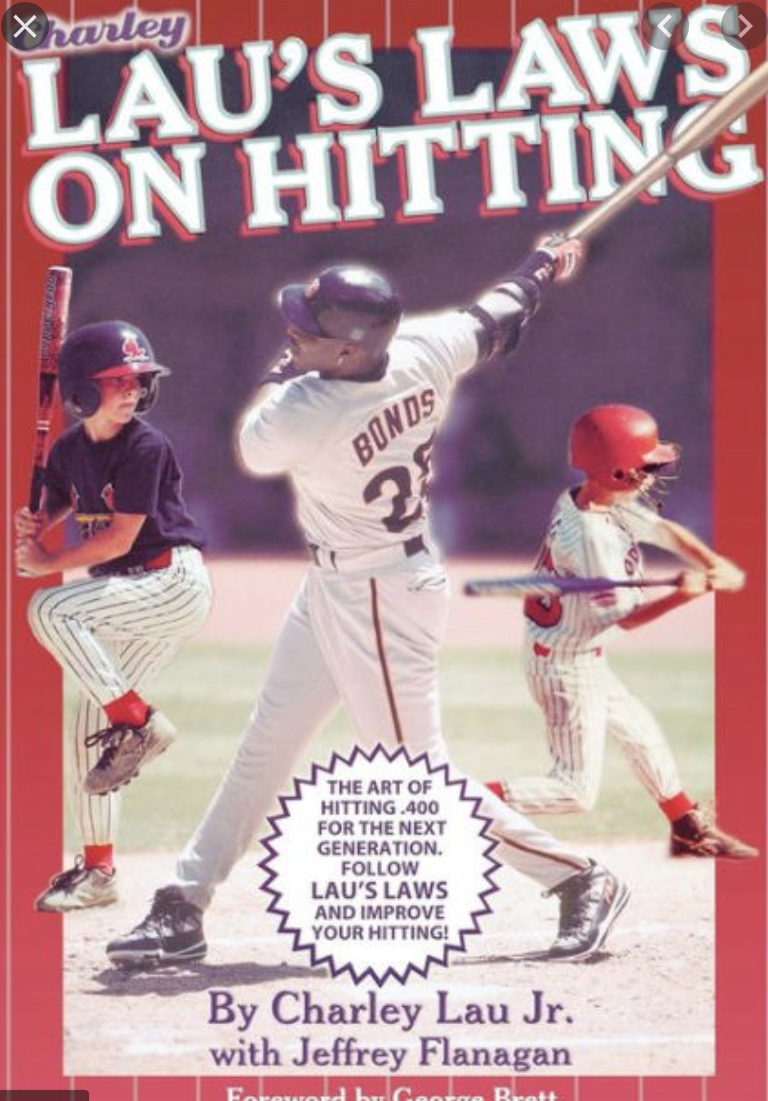

I think Charley Lau was the first hitting coach to really get “outside the box” and analyze what needed to be done to hit for a good average, although he had as many disbelievers as believers because his approach was very creative and out of a lot of guys’ comfort zones. He taught players to swing smoothly on what felt, to them, to be a downward plane (it wasn’t, it was a very flat plane) to get backspin on the ball, and to keep the bat in the contact zone as long as possible. He then preached letting the top hand go once contact was made. George Brett and Harold Baines both did OK hitting like that.

The swing plane theory was solid. If the ball is coming toward the plate at a slight downward angle (which, of course, it has to do thanks to the pitcher standing atop a small hill 60-feet 6-inches away) hitting with either an upward angle or a strict downward swing means the bat and the ball have to intersect at a precise place and at a precise time. We’re talking thousandths of a second to get it right. You’ve then taken a very difficult endeavor and made it even more improbable. Why not keep the bat on the same plane as the ball as long as you can? That way, you may not hit it square but you’ve got a better chance of actually hitting it. You could spot a Charley Lau disciple a mile away. They might as well have worn lime-green jerseys with LAU on the back. It was that obvious.

A whole new approach, and the dawn of a more analytic theory of hitting.

This, of course, doesn’t include any instruction on how to hit a split-finger, or a circle change, or two-seamer that runs, or anything that moves off that plane in an unexpected direction. Hitting a baseball is hard. It’s the most difficult thing to do in sports.

Even Michael Jordan, when he left the NBA to try baseball, was a Charley Lau disciple. I knew it the first time I saw video of him hitting in the batting cage for the White Sox.

And, as an aside, was Michael Jordan’s baseball adventure purely a publicity stunt? Could he play at all? By all accounts from his teammates in Birmingham and his manager there, Terry Francona (he’s pretty smart) he had all sorts of raw tools that can’t be taught. He just needed reps. He needed to play! He was 31 and hadn’t played the game since high school. To make the challenge even steeper, the White Sox signed him and sent him directly to Double-A, in the Southern League. That’s a notoriously difficult league with enormously long bus rides and brutally hot weather.

Francona basically said that if you gave him another year or two, Jordan would’ve made it to the big leagues. He was learning and adapting that fast. He hit .200 in Double-A as a pure rookie who hadn’t played baseball in 13 years. After his first year, though, there was a work stoppage and MLB was considering employing replacement players. MJ wanted nothing to do with that, so he hung up his spikes and put his Air Jordans back on. I’m still impressed by what he did. He’s an amazing athlete.

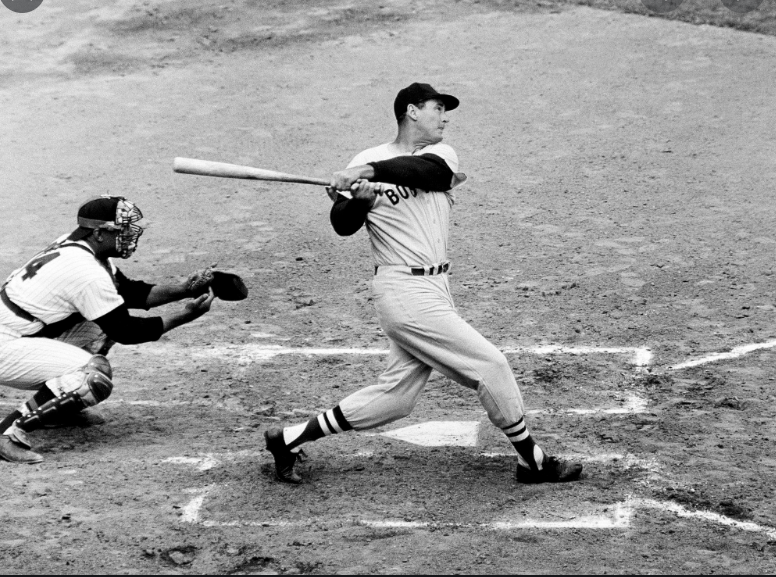

The great Ted Williams was a scientist about hitting, compared to other guys of that era (which was my father’s era). He studied how well he hit balls in various areas of the strike zone, and attempted to focus his swings on the “hot” zones were he almost always made good contact. His head was still, his balance was perfect, and as a hitter he was damn near perfection personified. He’s still the last player to hit .400 or better in the big leagues (way back in 1941) and I’m guessing he did that without any doting batting coach telling him anything about his swing. He figured it all out himself, but that’s why he’s a legend.

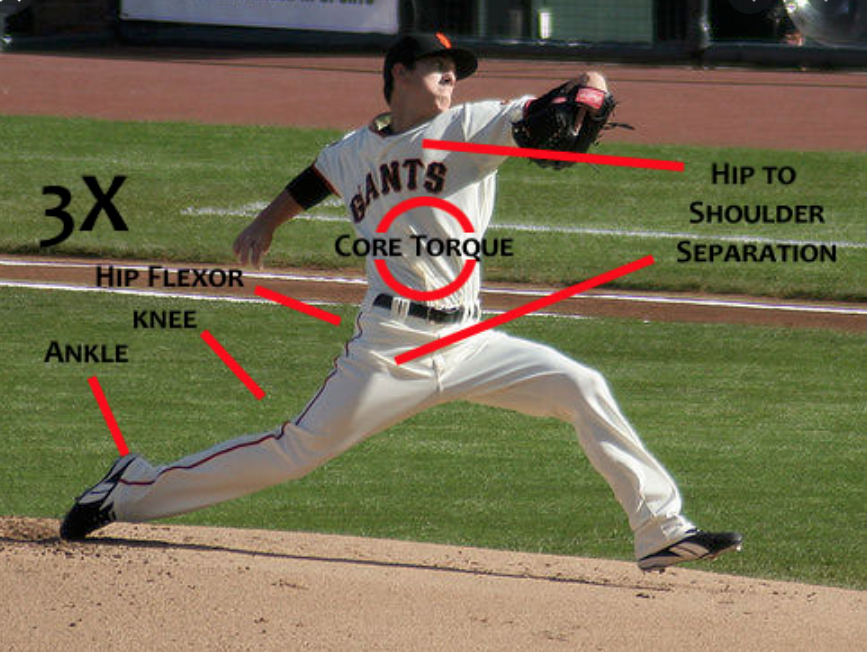

And then there’s pitching. It’s pretty much the same deal as hitting. For 100 years if you threw hard you had a chance to pitch professionally. It didn’t really matter what you looked like doing it. If you couldn’t throw hard, you had to find other ways of fooling hitters and missing bats. That’s really the essence of pitching. Fool batters, and miss their bats.

The level follow-through tells you all you need to know about Teddy Ballgame’s approach to hitting.

I can guarantee you that Bob Feller never went to any elite baseball skills camps as a kid. He did not play on an elite “travel team” either. He just threw baseballs really hard. By all accounts, and looking at old films, it’s the general consensus that Bob Feller threw 100 mph when he got to the Major Leagues at the age of just 17, in 1936.

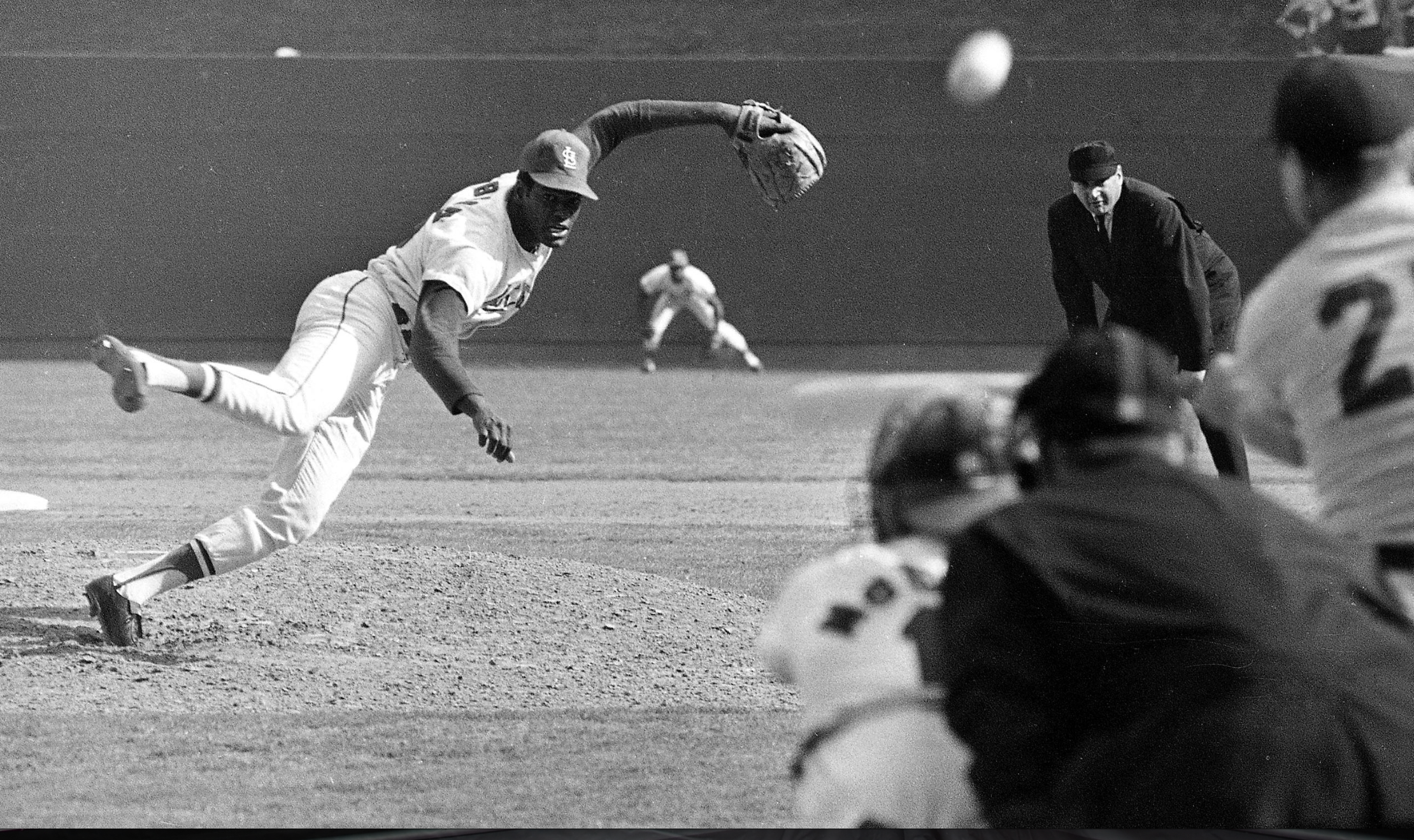

Bob Gibson, Don Drysdale, Juan Marichal, and Luis Tiant were intimidating pitchers during the 60s, and all of them had totally unique (and fairly crazy) deliveries. If Gibby were to sign as an 18-year old today, his first pitching coach in Class-A Rookie ball would more than likely do all he could to erase that wild follow-through he had, where his right leg would fully cross over his left as if he was running to first base. Marichal would likely be told to get rid of the ridiculous leg kick where his foot was as high as his head. Drysdale would be told to be more in balance and under control, and maybe stop throwing sidearm. And Tiant? Who knows? I don’t think he ever threw two pitches with the exact same delivery. It was like he was making it up as he went along. Some of that might fly today, but only if the pitcher was steadfast in his beliefs and willing to live with the consequences if it didn’t work. It would be all about balance points, hip flexing, leg drive, and other scientific facts they can show any pitcher on video. Of course, all those guys I just mentioned did nothing less than dominate. They were special. They were playing at a different level than normal guys. “Gifted” might be the word.

The line on Gibson was “He’d buzz a fastball under his own mother’s chin to move her off the plate.”

Some other pitchers of that era and the decades to follow were absolutely immaculate in their deliveries, surely with some help from pitching coaches but mostly via their own devices. Sandy Koufax, Tom Seaver, Steve Carlton, Jim Palmer, and others just naturally knew the best routine for themselves. They were elegant. I love using that word to describe a pitcher’s delivery. They were all elegant. Maybe Jim Palmer most of all.

Now, pitching coaches can rely on more computer power than Apollo 11 had to get to the moon. Super Slo-Mo, multiple angles, speed readings at the release point and at the plate. And the analytics have followed. Today’s successful big league pitching coaches are so prized by managers they end up in bidding wars during the offseason, like top free-agent players, taking the best offer and the best fit. The really good ones have ways of taking a mediocre big league pitcher (and a mediocre big league pitcher is a phenomenally good pitcher) and somehow finding another three miles per hour on his fastball, a bit more “bite” on his curve, and change-ups that look like Bugs Bunny threw them. It’s impressive to watch.

Power pitching is the hot thing now. I watch just about every Twins game and rarely do I see pitchers that throw under 94. Many throw in the high 90s. Some reach 100 without breaking a sweat. And then they snap off curveball that’s unhittable. I don’t know how anyone touches these guys, but the hitters have been doing their homework too. They’re so much more analytical and determined to find the solution.

I don’t know. I just threw the ball and hoped they didn’t hit it.

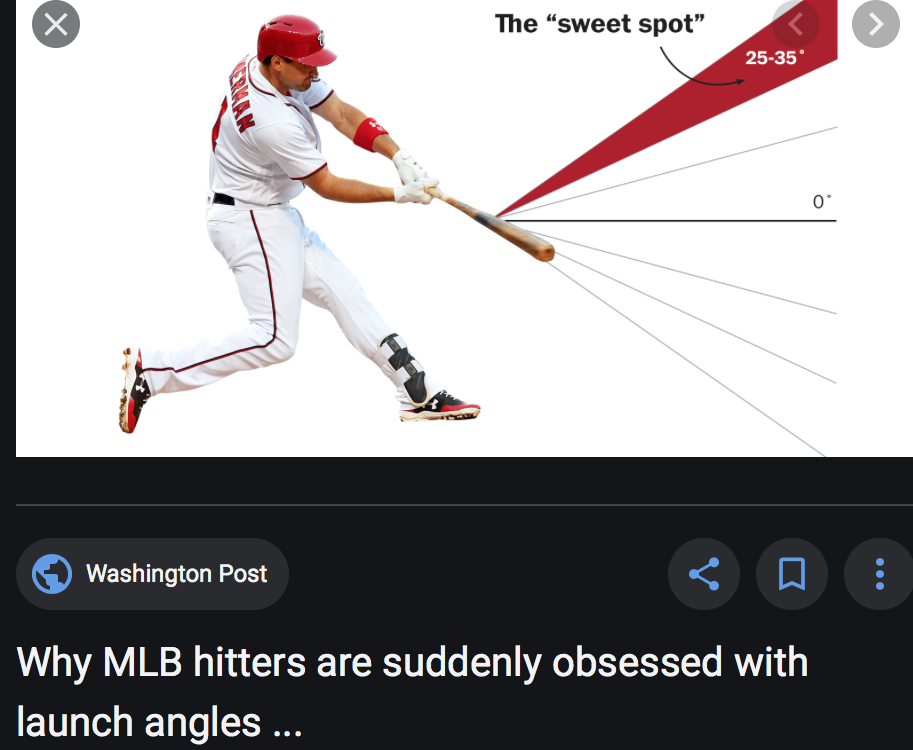

And those hitters work on tiny minute changes to their stances and swing to increase the chance of hitting a round baseball with a round bat so squarely it flies a long way. They’re all about launch angle, which is a term I never once heard until the last few years.

When I scouted for the Toronto Blue Jays, we had some standard numbers we looked for in pitchers. If we saw a guy who had an “average” big league fastball, we’d write up a report on him but we’d almost never write up a guy who was short of that number. What was “average” in 1982? About 88 mph. If I ever saw a high school or college kid hit 90+ I’d call Toronto that day to let them know the report was coming.

Funny thing on the Twins broadcast the other night. The announcers were talking about pitcher Jake Odorizzi and how his fastball “only” tops out around 93-94 mph now. One of the announcers said “With that lack of velocity, he’s had to reinvent himself as a finesse pitcher.” That’s eye-opening. The highest reading I ever saw on my Blue Jays radar gun was probably about 93 and when that popped up I couldn’t get to a phone fast enough to call GM Pat Gillick in Toronto. Now, in this era, that is known as finesse.

Running speed, arm strength, range in the field, and good fielding techniques haven’t changed much. Guys still run about the same, a good arm is still a good arm, and it all looks very much like when I played.

But then there’s hitting. I can’t fathom how good so many guys are now and how well honed their swings are. They still get fooled or overpowered, maybe 70% of the time, but they’re fundamentally much more solid with a lot more pop.

I, personally, was all about that flat approach that Charlie Lau and Ted Williams espoused. Keep the bat in the hitting zone and on the same plane as the pitch for as long as possible. Whenever I’d get power happy and try to hit long balls, my uppercut would creep in and I’d either hit pop-ups or dribblers, because my bat couldn’t match up with the plane of the ball. When I’d just focus on having a solid swing and balanced approach, I could hit bombs without thinking about it. Try to cream it, and you hit a one-hopper to the pitcher or a foul pop-up. Take a fundamentally solid swing, and it might go 430 feet. I don’t think I’d be very successful in this era of launch angles and bat speed, not to mention the fact that today’s MLB pitchers are powerful magicians. To me, they look unhittable. And hitting a baseball has always been hard.

It’s a different approach, that’s for sure

And this sort of instruction is starting really young now. When I was a kid I just ran out there and played baseball, all the time until I got to college. Our SIUE Cougar coaches, led by legendary Roy Lee, were the first real coaches I ever had. No one else tried to teach us much more than catching the ball, throwing the ball, and knowing which base to throw to. I was a little flabbergasted the first time Coach Lee and Coach Bob Hughes had us doing drills and simulations during batting practice. Up until then, BP had consisted of each of us getting in the cage and hitting 10 or 15 balls. However we wanted to do that. It was more about getting loose than trying to perfect anything.

Coach Hughes taught me more about using the whole field, instead of trying to pull everything, than anyone else ever came close to imparting. He taught me about pitch recognition, how to focus on a specific zone, and how to actually get in a pitcher’s head to figure out what he wanted to throw. If he favored a particular pitch you needed to spot that tendency, because he’d almost always go to it in a tight spot. It was hitting at a whole new level. It was kind of Zen, really. Amazing information to absorb.

And now kids under 10 are learning this stuff. They’re having their stances, weight shifts, and swings tinkered with and mastered by the time they’re 12 or 13. And when they turn pro, you get guys like Mike Trout and Bryce Harper.

This has all happened and evolved in just a few years. Analytics may be scoffed at by some, but they’ve changed the game and that’s OK. If you sort through the data long enough, you’ll find all the tendencies and the typical outcomes. So, defensively now, teams shift like crazy. It’s nothing totally new, teams shifted against Ted Williams throughout his career, but now it’s on a pitch-by-pitch and batter-by-batter basis. People are moving all around the field all the time. Is it good? Well, it works. Should it be banned? Absolutely no way. The hitters have to make adjustments. I’ve heard too many guys say “I’m paid to hit the ball out of the park, not bunt my way on or single against the shift.”

There’s one lonely guy on the left side of the field.

That may be true, and power hitters often just gum up the base paths because they don’t run well, but if they’re going to give you the entire left side of the field, you might want to figure out how to take advantage of that. I’ve seen the Twins doing that more and more. Some guys are willing to bunt or slap the ball, others aren’t comfortable with it. It’s amazing how many hard hit ground balls that would’ve been sure hits in my era, are now hit directly to a guy standing in a position that didn’t exist when I played. Just amazing. It most definitely would’ve driven me crazy as a hitter. I didn’t hit enough balls hard to have them wasted by the other team having a guy in short left field.

And the evolution continues. Watching the Twins this week I was struck by a new technique the pitchers are mixing in. It’s the high breaking ball. For my entire life a breaking ball up high in the zone was considered the worst possible pitch. It was like putting the ball on a platter when you spun one up there. But now, with these launch angle swings trying to go deep, it’s an effective pitch to big strong power guys. That’s evolution since last year!

It evolves. Throughout the history of baseball it’s gone through phases, when the pitchers were in command and when the hitters figured it out. It’s always been that way. It will continue to be that way. It’s just how the game works.

And I’m just thrilled to have games to watch. I don’t complain about any of the in-stadium noises or the cardboard cutout fans in the seats. I think it’s all fun. On the field, it’s still baseball. Guys still get dirty. Pitchers still try to strike you out and hitters try to solve that problem. It’s evolutionary. Let’s enjoy it…

That’s my message. Enjoy it. These times are so challenging, so difficult, and so off-the-charts most of us can’t recall anything like this. But baseball is still here. It’s America’s game. It’s comforting. It’s still a reminder, a harkening back to youth and our entire lives. It’s still baseball! Watch a game. Listen to one on the radio. Just let yourself soak it in and remember Teddy Ballgame, or Gibby, or Yaz, or The Mick, or if you’re younger think back to Maddux, and The Big Unit, and Junior. Heck, remember Bo Jackson. He was beyond belief. The dude ran up the outfield wall once! It’s the same game. The mound is still 60-feet and 6-inches from the plate. The bases are 90-feet apart. Pitchers throw hard and change speeds. Hitters try to adjust and make solid contact. Fielders do things I actually never dreamed of doing. It’s a beautiful game.

Watch a ballgame. It’s good for you and good for your soul.

See you next week, but I’ll most likely be late with that blog. We are all set to actually get out of the house and travel next week. Road trip!!! We’re driving up to Walker, Minn. on Sunday, to a resort on a big lake there. Walker’s about an hour north of Brainerd. Two other couples from the old neighborhood are meeting us there and we’re renting condos. We also have a pontoon boat rented for Tuesday. After three nights there, at Chase On The Lake, Barbara and I will head up to Roseau for a couple of days. I want to get back up there to solidify a few bits of background and characters for the new book, so I’m looking forward to that. I also want her to experience Roseau, and Warroad just down the road. I love it up there. We’re both really looking forward to it, and Boofus and Buster get to have their friend Kelsey come stay with them. As Willie Nelson sings, “On the road again. Just can’t wait to get on the road again…”

As always, there’s that pesky “Like” button just below here. It’s like a slow curve after a blazing fastball, but you can handle it. If you click on it, it’s like a solid line-drive into the gap. Well done!

Bob Wilber, at your service and still marveling at the evolution of this wonderful game.