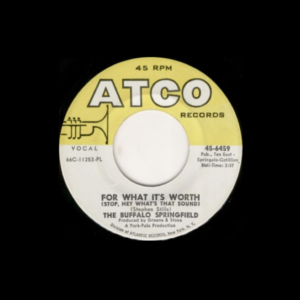

In late 1966 Stephen Stills sat down and wrote an anthem about specific events and the times our country was going through. The song was “For What It’s Worth” and he recorded it with his band Buffalo Springfield. These are those lyrics:

There’s something happening here

What it is ain’t exactly clear

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

I think it’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

There’s battle lines being drawn

Nobody’s right, if everybody’s wrong

Young people speaking their minds

Getting so much resistance, from behind

It’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

What a field-day for the heat

A thousand people in the street

Singing songs and carrying signs

Mostly say, hooray for our side

It’s time we stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

Paranoia strikes deep

Into your life it will creep

It starts when you’re always afraid

You step out of line, the man come and take you away

We better stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

It all sounds achingly familiar.

Also for the record, all these years later a lot of people think “For What It’s Worth” was written about the murder of students at Kent State University by the Ohio National Guard. That actually happened more than three years after “For What It’s Worth” was written and released. After Kent State, Stephen Stills’ new group, Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young, recorded and released the song “Ohio” to commemorate it. “Ohio” was written by Neil Young.

So the point here is this: I was born in 1956. I was a child of the 60s. Age wise, I didn’t fit neatly into a lot of the epic upheaval the country went through, but I remember it as if it were yesterday. When the Vietnam protests reached their high point, I was still just a bit too young to be there. In 1968, when it seemed like the entire world was falling apart and there was no foundation to lean upon, I was just 12. I remember the night Bobby Kennedy was killed. I remember the day Dr. King was killed. I remember the riots. I remember National Guard troops with rifles, and bayonets attached, facing off with unarmed kids. I watched as the Chicago police attacked demonstrators outside the Democratic convention, as if they were wading into war with a foreign adversary. I was too young to be in it, but I was part of it and very aware of it.

I was raised by two very special parents. They taught all of us some important lessons. We’re all in this together. You need to stand up for what is right. Hate is not an option. Silly little things like that.

As I got a little older, through high school, the Vietnam war was still raging and innocent young men were being shipped home in boxes by the plane load. I knew it was wrong, and by that time I was able to express my anger about it. My VW Beetle had plenty of peace signs and anti-war bumper stickers on it. I also knew I was likely next to go. It’s hard for anyone under 50 today to understand what that was like. We were powerless. When the government came for you and said “Time to report for duty” you had no choice other than Canada or some other country. All for a senseless war we were never going to win. I truly wanted to be a peace-loving hippie.

I had friends, as a kid, whose parents were very different than mine. Back then, I was aware that those kids already had been raised to believe what their mom and dad told them. It was very racial, very paranoid, and very destructive. I had friends whose families actually moved a mile or two within the same suburb because “the blacks” were buying houses just down the street. There was a lot of senseless hate, and I had never been taught that by my parents. I couldn’t understand it.

As the end of high school approached, the Selective Service (the organization that ran the military draft, and boy doesn’t that name sound so innocent) had at least adopted a lottery system. Instead of drafting every eligible 18-year-old boy, they ran 365 ping-pong balls through a machine and used birth dates to select a specific number of young men. The year before my eligibility, my birthday was well into the high 200s. I would not have been drafted. One year later, when I was on the spot, my birthday was in the top 10. There were ways to get deferments, but most of them required deceit (up to a felony depending upon the lie) or elite social standing that came with influential friends in high places. I was not going to use either of those approaches.

Then the war wound down, President Nixon was impeached and resigned, and the draft was discontinued before they called up the next “class” of soldiers. I was then, and am still now, incredibly fortunate.

I abhorred the Vietnam war, but I didn’t take that to the next level and hate the guys fighting over there. I admired them. I was stunned by their courage and dedication. I would have joined them had the draft continued, but even at the time I couldn’t fathom how I could be brave enough to do it. I knew a lot of guys who were drafted and ended up fighting. I couldn’t believe their stories, but the one thing those stories taught me was that they weren’t super heroes. They were just guys like me, mostly scared to death. Thrown into a hell no one over here, in our comfortable suburban homes, could imagine in our wildest nightmares. All for a cause nobody really understood.

It was such a tumultuous time, but as the 60s and 70s wore on, it felt like we as a people were figuring it out and getting much better as a society. There was a sense of “We’re better than this” and there was a lot of pride in knowing that peaceful protests could actually have an impact. Were there riots? More than most people today can even imagine. There was a lot of hate. A lot of reaction to oppression. A lot of pushback in a time when police and military men would charge peaceful protestors and attack them with force I couldn’t believe. But we felt we were getting better. That was a long time ago.

The last few weeks have felt like a time-travel deal. We’re right back to where we were. And here in the Twin Cities, we were the epicenter of it.

We watched a man of color get murdered by a law enforcement officer who seemed to relish what he was doing. I’d never seen anything like it, and could hardly believe it happened in Minneapolis. And the response by the public was swift.

Protest marches formed organically, and were attended by all types of citizens. Young, old, black, white, Christians, Jews, Muslims, you name it. They were angry, of course, but peaceful. What we all then witnessed was far too reminiscent of the Vietnam era. A tiny percentage of the participants used the peaceful marchers as cover, blending in until it was time to burn and loot. They succeeded in making everyone look bad, but I knew in my heart Minnesotans weren’t like that. Each day, hundreds or thousands from all backgrounds would show up in the morning to clean up. Food drives that had been organized to feed dozens were overwhelmed with enough food to feed thousands. The peaceful marches continued, arm in arm, shoulder to shoulder, but the opposition began to look more and more like a heavily armed military and the whole thing just got more and more frightening. And it spread across the country.

We live on the other side of the Twin Cities from where most of the protests happened in Minneapolis. But the line in Stephen Stills’ song that says “Paranoia strikes deep” certainly applied.

Early on, to keep outside agitators from easily driving into St. Paul or Minneapolis, they closed the interstate highways from late afternoon until morning. I-94, the major East-West freeway here, was closed and if you drove to the closure point, you had to exit right here in Woodbury. If people bent on destruction were trying to get to Minneapolis, they’d be forced off the road just a few miles from our peaceful little neighborhood. Paranoia strikes deep, indeed.

For a long string of nights, we joined most of our neighbors by keeping all of our outside lights on, whether it was just porch lights or (in our case) spotlights that lit up our entire backyard. We heard the helicopters circling. Every time we’d hear a siren we didn’t think “There must have been a wreck, or a fire, or something.” Those are normal reactions in a sleepy suburb. This was not normal.

I stayed up until at least 3:00 am for many nights in a row. I couldn’t sleep anyway, and we both “heard noises” and worried, so I stayed up and kept watch. I could hit a 100 mph fastball with a baseball bat in my prime and figured one of those Bob Wilber autographed U-1 model Louisville Sluggers would be my weapon of choice if anyone so much as peered into one of our windows. Paranoia strikes deep. It really does.

We’re getting through it. George Floyd was not conveniently forgotten. Minnesotans rose to the occasion and those bent on anarchistic destruction gave up and went home. And now we recover. We’re still trying to do that.

All that pride from the 60s and 70s, when we thought we were really making a difference and our generation would get beyond racism, prejudice, judgement, and abuse seems long gone. Here we are again. Maybe this time we’ll learn. It certainly feels like we can. I hope that’s true.

My parents didn’t see people in terms of color. They gave no thought to social strata or wealth. They just saw people, the good and the bad, and taught us to be inclusive and fair. Skin color, sexual orientation, religion, political beliefs, and other prejudicial nonsense was not part of my life. None of that makes any sense to me.

George Floyd died on the street in Minneapolis. It’s still hard to believe and nearly impossible to watch. But I’m proud of Minnesota for how the vast majority stood up for him, and stood up for our state and our cities. These are good people. I’m proud to be one of them.

That’s my rant for today. It felt important to do this.

If you perused this and liked it, there’s that “Like” button at the top of this blog. It would be great if you clicked on that.

We’re OK. We’re better for this. George Floyd did not die in vain. And we must remember so many other innocent unarmed citizens of color who have been profiled, or singled out, or manhandled, or injured, or murdered. It’s tragic. We have to learn. We have to! We’re better than this.

Bob Wilber, at your service.